2025-02-11 18:33:20,某些文章具有时效性,若有错误或已失效,请在下方留言。We’re going to build a macOS app that lets users write Markdown and see exactly how it looks as they type. More importantly, we’re going to do so using test-driven development, so get ready to write some tests!

我们将构建一个 macOS 应用程序,让用户可以编写 Markdown,并在输入时清楚地看到它的外观。更重要的是,我们将使用测试驱动开发来实现这一点,所以请准备好编写一些测试!

To follow along, create a new macOS project in Xcode using the App template, naming it LiveScribe. Make sure you don’t select anything for Testing System – I want to do that manually, so you can see how it’s done if you have an existing project.

请使用 App 模板在 Xcode 中创建一个新的 macOS 项目,并将其命名为 LiveScribe。请确保不要选择测试系统的任何选项–我想手动选择,这样您就可以看到如果您有一个现有项目是如何完成的。

The basics of TDD TDD 的基础知识

Test-driven development uses a simple but powerful approach that dramatically changes the way we write software. It breaks coding down into three stages called Red, Green, Refactor:

测试驱动开发使用一种简单而强大的方法,极大地改变了我们编写软件的方式。它将编码分成三个阶段,分别称为 “

- The Red stage has us write a test that doesn’t pass.

红色 阶段让我们编写一个无法通过的测试。 - The Green stage has us write just enough app code to make the test pass.

在 “绿色 “阶段,我们只需编写足够的应用程序代码,就能使测试通过。 - The Refactor stage has us clean up our app code so that it’s the best we can make it.

重构 阶段让我们清理应用程序代码,使其达到最佳状态。

Those three stages happen for every small piece of app code you write, and it’s quite the reverse of how many people approach writing tests – often we write a whole bunch of production code, then write tests for that code as an afterthought.

这三个阶段发生在你编写的每一小段应用程序代码中,而这与许多人编写测试的方法恰恰相反–我们通常会编写一大堆生产代码,然后事后才为这些代码编写测试。

While that can work just as well in terms of getting a solid end result, writing tests afterwards often leads to the problem where you find certain code is really hard to test simply because it wasn’t written with tests in mind. With TDD, every piece of code we write must be testable, so this problem can’t occur.

虽然这 可以 获得可靠的最终结果方面同样有效,但事后编写测试常常会导致这样的问题:你会发现某些代码真的很难测试,原因很简单,因为编写时没有考虑到测试。有了 TDD,我们编写的每一段代码都必须是可测试的,这样就不会出现这种问题了。

Key to the whole TDD process is the word “refactor”, which has a very specific meaning that many developers just seem to ignore. Refactoring your code means changing it to be simpler, faster, or more flexible while ensuring that its functionality remains the same. The problem is that without solid tests in place, there’s no way of actually being sure the functionality is the same!

整个 TDD 过程的关键是 “

Anyway, we’ll be using TDD for our whole app, including a small amount of UI testing. Before we start, I should say that UI testing has three major annoyances:

总之,我们将在整个应用程序中使用 TDD,包括少量用户界面测试。在开始之前,我想说用户界面测试有三大弊端:

- It needs to be done using the old XCTest framework, rather than the newer Swift Testing framework. Hopefully this will change in the future!

这需要使用旧的 XCTest 框架,而不是较新的 Swift 测试框架。希望将来会有所改变! - It’s quite annoying on macOS, because it takes control of your Mac while running. After our UI tests pass we’ll be disabling them for the rest of the stream, to avoid this getting too annoying.

在 macOS 上,这个功能非常恼人,因为它会在运行时控制你的 Mac。用户界面测试通过后,我们将在剩余的数据流中禁用它们,以避免其变得过于烦人。 - UI tests are extremely flaky because they literally scan the screen using the same accessibility layer as VoiceOver; you need to give them a little more leeway than with unit tests.

用户界面测试非常不稳定,因为它们使用与 VoiceOver 相同的无障碍层扫描屏幕;与单元测试相比,你需要给它们更多的回旋余地。

Proof of life 生命的证明

We’re going to start with some UI tests, all of which will be very simple. Remember, our first TDD step is to write tests that don’t pass – we never write production code until we have a failing test we’re trying to fix.

我们将从一些用户界面测试开始,所有测试都将非常简单。请记住,我们 TDD 的第一步就是编写未通过的测试–在我们尝试修复未通过的测试之前,我们永远不会编写生产代码。

Start by going to the File menu and choosing New > Target. Enter “test” in the Filter box, and select UITestingBundle. Name it LiveScribeUITests and click Finish to create it.

首先进入 “File “菜单,选择 “New > Target”。在过滤器框中输入 “test”,然后选择 UITestingBundle。将其命名为 LiveScribeUITests,然后单击 “Finish “创建。

![图片[2]-LiveScribe-Stewed Noodles 资源](https://oss.stewednoodles.com/2025/02/11/StewedNoodles20250211144618.webp)

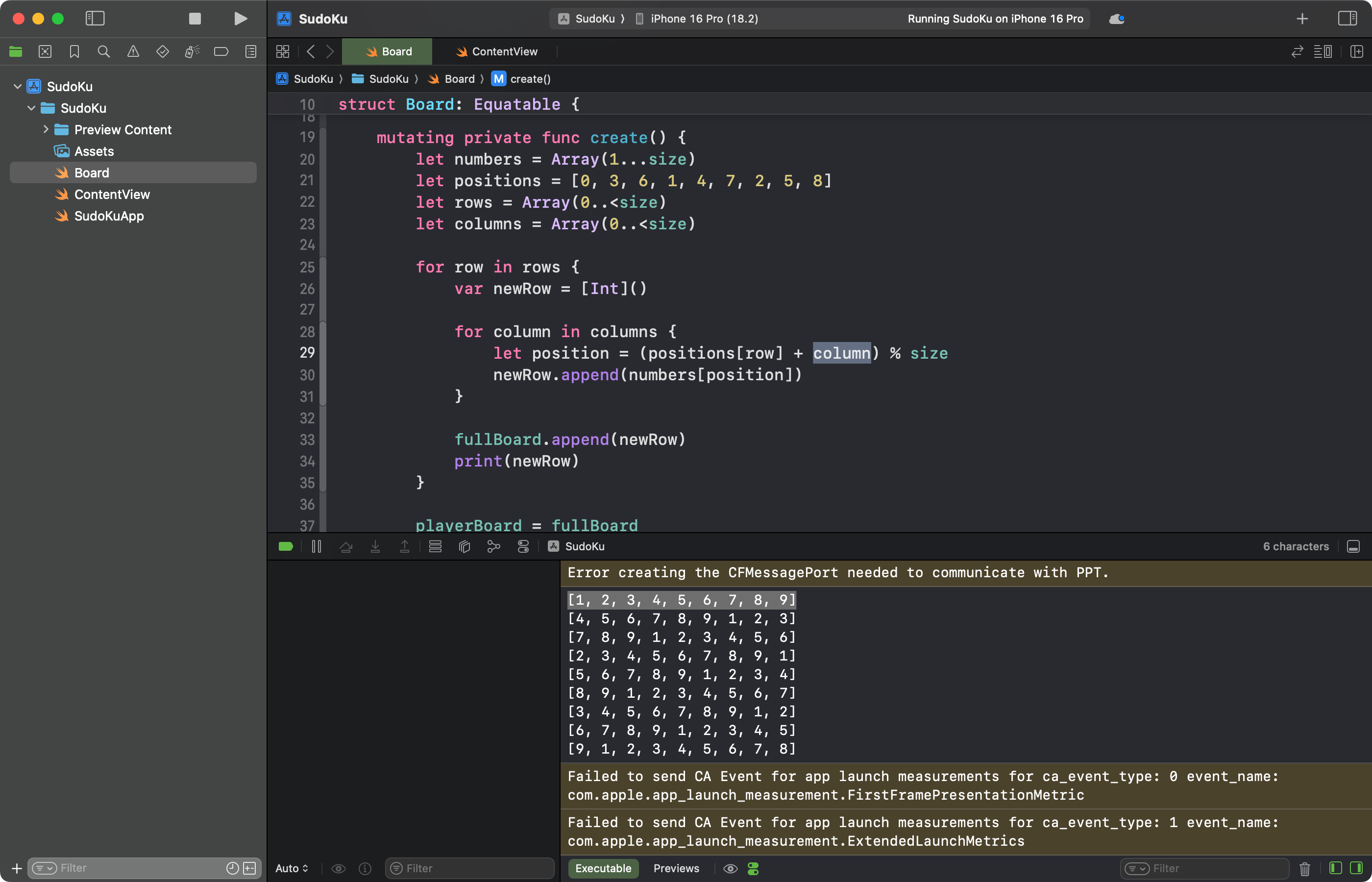

Xcode will create some helpful template code for you here. The whole LiveScribeUITestsLaunchTests.swift file is there to show you how to take screenshots if things go wrong, but our UI tests are so trivial we won’t need that so please just delete that whole file.

Xcode 会在此处为您创建一些有用的模板代码。整个 LiveScribeUITestsLaunchTests.swift 文件的作用是告诉你如何在出错时截图,但我们的 UI 测试非常琐碎,不需要这些,所以请删除整个文件。

Over in LiveScribeUITests.swift there are a handful of important things:

在 LiveScribeUITests.swift 中,有几件重要的事情:

- The

setUpWithError()method is where we perform any configuration for our app before any tests run.setUpWithError()方法是我们在测试运行前对应用程序进行配置 的方法。 - Its counterpart is

tearDownWithError(), which cleans up after a test is run.

与之对应的是tearDownWithError(),它会在测试运行后进行清理 。 - The

testExample()method is an example test. The method name starts with the word “test”, which is required by XCTest to know it’s a test that should be run. This creates and launches an instance of our app.testExample()方法是一个示例测试。该方法的名称以 “test “开头,XCTest 需要知道这是一个应该运行的测试。该方法将创建并启动应用程序的一个实例。 - The

testLaunchPerformance()method is an example performance test, in this case checking how long it takes for the app to launch.testLaunchPerformance()方法是一个性能测试 示例,在本例中用于检查应用程序启动所需的时间。

We need to do a little cleaning to get this ready for us here, so please make the following changes:

我们需要做一些清理工作,以便在这里为我们做好准备,因此请做以下更改:

- Delete the whole

testLaunchPerformance()method – our app will be so small that it will launch instantly.

删除整个testLaunchPerformance()方法 – 我们的应用程序将非常小,可以立即启动。 - Also delete the whole

tearDownWithError()method; we won’t have any clean up to do.

同时删除整个tearDownWithError()方法;我们就不用再做任何清理工作了。 - Move the

@MainActorannotation fromtestExample()up to the whole class, so it all runs on the main actor.

将@MainActor注解从testExample()移至整个类,这样所有操作都能在主角色上运行。 - Move the

let app = XCUIApplication()line up to be a property of theLiveScribeUITestsclass, because all our tests need that.

把let app = XCUIApplication()这一行移到LiveScribeUITests类的属性上,因为我们所有的测试都需要它。 - Move the

app.launch()in into thesetUpWithError()method, because all our tests will need the app to launch.

将app.launch()移到setUpWithError()方法中,因为我们的所有测试都需要启动应用程序。 - Finally, delete the shell of

testExample(), along with all the comments floating around.

最后,删除testExample()的外壳,以及所有漂浮的注释。

This should be all that remains:

应该只剩下这些了:

import XCTest

@MainActor

final class LiveScribeRemakeUITests: XCTestCase {

let app = XCUIApplication()

override func setUpWithError() throws {

continueAfterFailure = false

app.launch()

}

}

That’s a nice and clean starting point for us to write our own tests.

这为我们编写自己的测试提供了一个简洁明了的起点。

Speaking of which, let’s write one now. Remember, this test is going to fail because we haven’t written any production code yet!

说到这里,让我们现在就写一个。记住,这个测试会失败,因为我们还没有编写任何生产代码!

Our first test will be to check there’s an input text view, where the user can write their Markdown text. Add this to the LiveScribeUITestsclass now:

我们的第一个测试是检查是否有输入文本视图,用户可以在该视图中写入 Markdown 文本。现在就把它添加到LiveScribeUITests类中:

func testInputExists() {

XCTAssertEqual(app.textViews.count, 1, "There should be 1 TextEditor for the user to type into.")

}

We’ll look at what does in a moment, but first let’s try it out. When you press Cmd+S to save the code, a small diamond should appear in the line number gutter – this is a button you can press to run the test. So, press it now!

稍后我们将了解它的作用,但首先让我们试一试。按下 Cmd+S 保存代码后,行号沟中会出现一个小菱形–这是您可以按下运行测试的按钮。现在就按下它!

That will build and launch our app, then run the test against it. This is where things get annoying – it will dim your whole Mac display while the test runs, making other work impossible. Remember, it’s literally scanning the screen using the macOS accessibility system, so if we get in the way by clicking on stuff it could break the test.

这将构建并启动我们的应用程序,然后对其运行测试。这就是令人烦恼的地方–当测试运行时,它会调暗整个 Mac 显示屏,导致其他工作无法进行。请记住,它实际上是在使用 macOS 辅助系统扫描屏幕,因此如果我们点击某些东西,就会妨碍测试。

Once the test completes you’ll see our diamond button has turned into a red and white cross icon, because our test failed. Again, that’s expected!

测试完成后,你会看到我们的钻石按钮变成了红白相间的十字图标,因为我们的测试失败了。这也是意料之中的!

![图片[3]-LiveScribe-Stewed Noodles 资源](https://oss.stewednoodles.com/2025/02/11/StewedNoodles20250211150858.webp)

Before we fix the problem, let’s look at the four key parts of the code we just wrote:

在解决问题之前,我们先来看看刚才编写的代码中的四个关键部分:

- The method name starts with the word “test”. Again, this is a requirement of XCTest; without that word at the start, it wouldn’t know this was code it could run.

方法名称以 “test “开头。这也是 XCTest 的要求;如果开头没有这个词,它就不知道这是可以运行的代码。 - The

app.textViews.countis a query – it looks like we’re reading a static array calledtextViews, but really it kicks off that whole scanning process and counts the result. This will be important shortlyapp.textViews.count是一个查询语句,看起来像是在读取一个名为textViews的静态数组,但实际上它启动了整个扫描过程,并对结果进行计数。这一点很快就会变得很重要 - The

XCTAssertEqual()function is an assertion – it compares parameter 1 against parameter 2, and considers the test a failure if they aren’t equal.XCTAssertEqual()函数是一个断言 –它将参数 1 与参数 2 进行比较,如果不相等,则认为测试失败。 - The third parameter is a string that will be printed if the test fails. This is helpful to remind yourself what the correct behavior ought to be.

第三个参数是一个字符串,如果测试失败,将打印该字符串。这有助于提醒自己正确的行为应该是什么。

We’ve just finished the first stage of TDD: we’ve got a test failure. Now we need to move onto the second stage, which is to write just enough code to pass the test.

我们刚刚完成了 TDD 的第一阶段:测试失败。现在我们需要进入第二阶段,即编写足够的代码来通过测试。

That means opening up ContentView.swift and creating a TextEditor view with something inside. First, create a new property to store the text editor’s content:

这意味着打开 ContentView.swift,创建一个包含内容的TextEditor视图。首先,创建一个新属性来存储文本编辑器的内容:

@State private var input = ""

Now replace the body property with this:

现在用以下内容替换body属性:

TextEditor(text: $input)

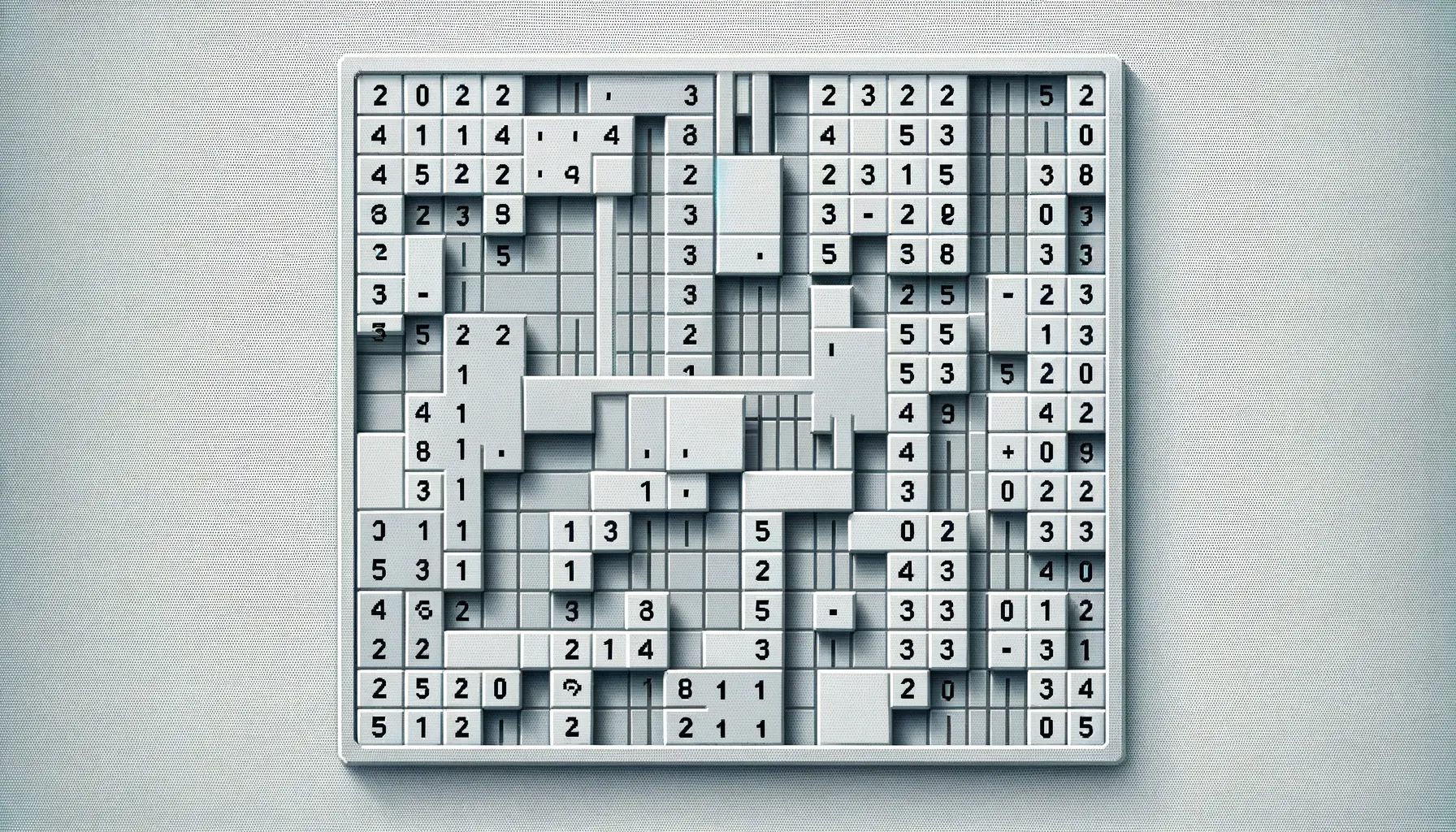

That’s the bare minimum we need to do to make the test pass, so go back to the test file and click the red diamond to re-run the test. Again your screen will be taken over as the test runs, but when it completes the red cross should become a green check mark because the test passes – there is one text view.

这是使测试通过所需的最基本步骤,因此请返回测试文件,点击红钻重新运行测试。测试运行时,你的屏幕将再次被占用,但测试完成后,红叉应变成绿色复选标记,因为测试通过了–只有一个文本视图。

![图片[4]-LiveScribe-Stewed Noodles 资源](https://oss.stewednoodles.com/2025/02/11/StewedNoodles20250211153502.webp)

Upping the test complexity 提高测试的复杂性

In our app we need a second view, which will show the output as a web view. So, let’s write a second failing test:

在我们的应用程序中,我们需要第二个视图,它将以 Web 视图的形式显示输出结果。因此,让我们编写第二个失败测试:

func testOutputExists() {

XCTAssertEqual(app.webViews.count, 1, "There should be 1 WKWebView for the user to see their rendered output.")

}

That’s very similar to the previous test, except now we’re looking for web views rather than text editors.

这与之前的测试非常相似,只不过现在我们要找的是网络视图,而不是文本编辑器。

This is where things get a smidge tricky, because SwiftUI doesn’t currently have a WebKit wrapper. From what I can see that will change at WWDC25, so if you’re following this in the future you might find there’s an easier route here!

这就是事情变得有点棘手的地方,因为 SwiftUI 目前还没有 WebKit 封装器。据我所知,这将在 WWDC25 上发生变化,所以如果你将来关注这个问题,你可能会发现这里有一条更简单的途径!

First, create a new SwiftUI view called SimpleWebView in your main app target, add import WebKit to the top, then give it this code:

首先,在主应用程序目标中创建一个名为SimpleWebView的新 SwiftUI 视图,在顶部添加import WebKit,然后为其添加以下代码:

struct SimpleWebView: NSViewRepresentable {

func makeNSView(context: Context) -> WKWebView {

WKWebView()

}

func updateNSView(_ webView: WKWebView, context: Context) {

}

}

That’s not really a useful web view just yet because it doesn’t show any content, but that’s the point – we write just enough code to make our test pass.

这还不是一个真正有用的网络视图,因为它没有显示任何内容,但这就是问题所在–我们只需编写足够的代码,就能让测试通过。

Back in ContentView we can add that to our body property alongside the previous text editor:

回到ContentView中,我们可以将其与之前的文本编辑器一起添加到我们的body属性中:

TextEditor(text: $input)

SimpleWebView()

If you run the app with Cmd+R you should see both views appear correctly, so now go ahead and try running the testOutputExists()test.

如果使用 Cmd+R 运行应用程序,应该可以看到两个视图都正确显示,现在继续尝试运行testOutputExists()测试。

Now, you might think it will pass, but it won’t – despite our code being trivial, the test is still failing. What gives?

现在,你可能认为测试会通过,但事实并非如此–尽管我们的代码微不足道,但测试仍然失败了。什么原因?

Well, there are actually several problems here occurring all at once. The first and most important is that WKWebView is one of those UI components that very much likes to do its own thing. In technical terms, WKWebView does its work out of process, which means it does its CPU and memory work away from your main application, so the app stays responsive while the web view is loading.

实际上,这里同时存在几个问题。首先,也是最重要的一个问题是,WKWebView是一种非常喜欢自作主张的 UI 组件。用技术术语来说,WKWebView是在进程外工作的,这意味着它的 CPU 和内存工作是在主程序之外进行的,因此应用程序在网页视图加载时仍能保持响应。

This is an important feature for performance, but really screws with XCTest’s screen scanning – it runs the app and immediately looks for a web view, but won’t find one because it hasn’t finished being created yet.

对于性能而言,这是一项重要功能,但却会严重影响 XCTest 的屏幕扫描功能–运行应用程序后,它会立即查找网络视图,但却找不到,因为网络视图尚未创建完成。

So, this first problem isn’t our user interface, it’s our test code. To fix it, we need to tell XCTest to chill out a little – to give the web view chance to be created.

所以,第一个问题不是 我们的用户界面,而是我们的测试代码。要解决这个问题,我们需要让 XCTest 稍微冷静一下,给网络视图一个创建的机会。

Change the test code to this:

将测试代码改为

func testOutputExists() {

let webViewExists = app.webViews.firstMatch.waitForExistence(timeout: 1)

XCTAssertTrue(webViewExists, "There should be 1 WKWebView for the user to see their rendered output.")

}

This is where you can see the scanning system in action more closely: we’re accessing the first item from all the web views, but we’re accessing it in a way that allows XCTest to wait one second for it to appear.

在这里,您可以更近距离地看到扫描系统的运行:我们从所有网页视图中访问第一个项目,但我们访问它的方式是让 XCTest 等待一秒钟让它出现。

But if you run the test again, it’s still failing – XCTest simply can’t see the web view.

但如果再次运行测试,结果还是失败–XCTest 根本无法看到网络视图。

This is where we need to move onto the second problem: if you never ask the web view to load anything, it’s never created. In our case we made a SimpleWebView wrapper that creates a WKWebView, but it doesn’t actually make the web view on the screen until we tell it to load something.

这就是我们需要解决的第二个问题:如果你从未要求网络视图加载任何东西,那么它就永远不会被创建。在我们的案例中,我们创建了一个SimpleWebView封装器,它可以创建一个WKWebView,但在我们要求它加载任何东西之前,它并不会真正在屏幕上创建 Web 视图。

Again, we need to do just enough work to make our test pass, so add this line of code to the updateNSView() method:

同样,我们只需要做足够多的工作就能使测试通过,因此请在updateNSView()方法中添加这行代码:

webView.loadHTMLString("", baseURL: nil)

That tells the web view to load nothing, but nothing is still something as far as WebKit is concerned, so that’s enough to make the web view load.

这就告诉网络视图不加载任何内容,但对于 WebKit 来说,”无 ” 仍然是 “有”,因此这足以让网络视图加载内容。

Now try the test again. And… it’s still failing?!

现在再试一次。结果……还是失败?

This is where we hit our third problem: for some reason, loading a local string is considered networking, and on macOS that’s disallowed by default. So, to fix the third problem we need to tell macOS that our app will try to make outgoing network connections, which means you need to:

这就是我们遇到的第三个问题:由于某些原因,加载本地字符串会被视为联网,而在 macOS 上,默认情况下这是不允许的。因此,要解决第三个问题,我们需要告诉 macOS,我们的应用程序将尝试建立外向网络连接,这意味着你需要

- Go to the LiveScribe target.

转到 LiveScribe Target。 - Select Signing & Capabilities.

选择 “Signing & Capabilities”。 - Scroll down to App Sandbox.

向下滚动到 App Sandbox。 - Check the box next to Outgoing Connections (Client).

选中 “Outgoing Connections (Client)”旁边的复选框。

And now the test should pass: we’re waiting for the web view to exist, making it load an empty string, and also allowing networking connections, and the combination of those three is just enough for our test to pass. Phew!

现在测试应该通过了:我们正在等待网络视图的存在,让它加载一个空字符串,同时允许网络连接,这三者的结合足以让我们的测试通过。呼

![图片[5]-LiveScribe-Stewed Noodles 资源](https://oss.stewednoodles.com/2025/02/11/StewedNoodles20250211161344.webp)

Let’s write a third UI test, which will be our most complicated: when we write something into the text editor, is that text reflected in the web view?

让我们来编写第三个用户界面测试,这将是最复杂的测试:当我们在文本编辑器中写入一些内容时,这些文本是否会反映在网页视图中?

Making this work means introducing a handful of extra pieces of XCTest:

要做到这一点,需要在 XCTest 中引入一些额外的组件:

- We need to activate the text editor, so it’s focused for typing.

我们需要激活文本编辑器,让它集中精力打字。 - We then need to type something in there.

然后,我们需要在其中输入一些内容。 - And finally we need to verify that the web view contains the correct output.

最后,我们需要验证网络视图是否包含正确的输出。

We’ll write this piece by piece, starting with two easy parts: the method signature, and a check to make sure the web view has loaded already.

我们将逐条编写,首先从两个简单的部分开始:方法签名和检查以确保网络视图已经加载。

Add this to the LiveScribeUITests class:

将此添加到LiveScribeUITests类中:

func testOutputMatchesInput() {

_ = app.webViews.firstMatch.waitForExistence(timeout: 1)

// more code to come

}

Our first task is to activate the text view, so any text that gets typed goes to the correct place. This can be done using the tap() method of XCTest queries, so add this to the test:

我们的第一项任务是激活文本视图,这样输入的任何文本都会转到正确的位置。这可以使用 XCTest 查询的tap()方法来完成,因此请将其添加到测试中:

app.textViews.firstMatch.tap()

Next, we need to type some text in there, which is done using typeText(). You can use this on a particular element if you want, but there really isn’t much point because only one thing can have keyboard focus at a time so this is sufficient:

接下来,我们需要在其中键入一些文本,这可以使用typeText() 来完成。如果你愿意,可以在特定元素上使用此功能,但实际上没有太大意义,因为同一时间只能有一个元素拥有键盘焦点,所以使用此功能就足够了:

app.typeText("Hello, world!")

And now we want to make our assertion: does the web view contain the text “Hello, world!”? This is done through the staticTexts query, and we can assert against its exists property because all we care about it that it exists.

现在我们要断言:网络视图是否包含文本 “Hello, world!”?这可以通过staticTexts查询实现,我们可以针对其exists属性进行断言,因为我们只关心它是否存在。

So, finish the test with this code:

因此,请用以下代码完成测试:

XCTAssertTrue(app.webViews.firstMatch.staticTexts["Hello, world!"].exists, "Typing into the text editor should create matching output.")Done! That ought to fail, so we can move onto the next stage of TDD: writing just enough code to make that test pass.

完成!这个测试应该会失败,因此我们可以进入 TDD 的下一阶段:编写足够的代码使测试通过。

Here’s where I want to explore those words “just enough”, because it’s something I’ve seen folks get wrong a lot.

在这里,我想探讨一下 “恰到好处 “这个词,因为这是我见过的人们经常犯错的地方。

You see, the correct, TDD-aligned code to write now is to open SimpleWebView.swift and change its updateNSView() method to this:

你看,现在要写的与 TDD 一致的正确代码是打开 SimpleWebView.swift,将其updateNSView()方法改成这样:

webView.loadHTMLString("Hello, world!", baseURL: nil)

That is the bare minimum we need to do make our test pass, which is what TDD requires us to do. force text views to load.

强制加载文本视图。

Note: Sometimes you might find you need to add _ = app.textViews.firstMatch.waitForExistence(timeout: 1) to your tests in order for the text view to definitely load. This appears to be highly dependent on how fast your Mac is, so I’d suggest adding it to be sure!

注意:有时你可能会发现需要在测试中添加_ = app.textViews.firstMatch.waitForExistence(timeout: 1)才能确保文本视图加载完成。这似乎在很大程度上取决于 Mac 的速度,因此我建议添加它以确保万无一失!

Anyway, the problem here isn’t our code; our code does exactly what it’s supposed to do. The problem is the test: we’re testing for a specific, fixed input, which doesn’t actually test what we wanted – we wanted to test that the output matches the input, not that the output matches some specific value.

总之,问题不在于我们的代码;我们的代码做了它应该做的事情。问题出在 测试 上:我们测试的是一个特定的、固定的输入,这实际上并没有测试出我们想要的结果–我们想要测试的是输出与输入是否匹配,而不是输出与某个特定值是否匹配。

One option here is to make a little array of possible strings and loop through them all, but that just starts a testing arms race – it’s not hard to write code to fake passing this kind of test.

一种方法是创建一个包含所有可能字符串的小数组,然后在所有字符串中循环,但这只会引发测试军备竞赛–编写代码伪造通过此类测试并不难。

Instead, a better solution is to generate some random text on every run, so there’s no possibility of faking it – the output must match the input, because we can’t tell ahead of time what the input might be.

相反,更好的办法是在每次运行时生成一些随机文本,这样就不可能作假了–输出必须与输入相匹配,因为我们无法提前知道输入可能是什么。

So, change the test to this:

因此,把测试改成这样:

func testOutputMatchesInput() {

_ = app.webViews.firstMatch.waitForExistence(timeout: 1)

let targetText = UUID().uuidString

app.textViews.firstMatch.tap()

app.typeText(targetText)

XCTAssertTrue(app.webViews.firstMatch.staticTexts[targetText].exists, "Typing into the text editor should creating matching output.")

}

Now we’re creating a random UUID, which means our test will fail – our little WKWebView hack just isn’t good enough.

现在,我们正在创建一个随机 UUID,这意味着我们的测试将失败–我们的WKWebView小黑客还不够好。

To make this test pass we actually need to make the output and input stay in sync, which means making a handful of changes to our app code.

为了让测试通过,我们实际上需要让输出和输入保持同步,这意味着要对应用程序代码做一些修改。

First, we need to make SimpleWebView track a string to render by adding this property:

首先,我们需要通过添加此属性使SimpleWebView跟踪要渲染的字符串:

var content: String

If you’re using Xcode’s previews, passing any value here is fine:

如果您使用的是 Xcode 的预览,在这里传递任何值都可以:

#Preview {

SimpleWebView(content: "Testing")

}

Second, we need to amend the updateNSView() method so our web view loads the requested content rather than hard-coding something:

其次,我们需要修改updateNSView()方法,以便我们的网络视图能加载请求的内容,而不是硬编码:

webView.loadHTMLString(content, baseURL: nil)

And third, we need to change ContentView so that we send our HTML input into the web view, like this:

第三,我们需要更改ContentView,以便将 HTML 输入发送到 Web 视图,就像这样:

SimpleWebView(content: input)

That will trigger updateNSView(), which will in turn cause the refreshed content to be loaded into the web view.

这将触发updateNSView(),进而将刷新的内容加载到网络视图中。

And now the test will pass – nice!

现在测试可以通过了–很好!

Before we’re done with the UI part of our app, let’s write one more test. Our current app layout isn’t great because text is usually much longer than it is wide, but we can fix that by placing our two views side by side and letting users adjust their size.

在完成应用程序的用户界面部分之前,让我们再写一个测试。我们当前的应用程序布局并不理想,因为文本通常比宽度长很多,但我们可以将两个视图并排放置,让用户调整它们的大小,从而解决这个问题。

![图片[6]-LiveScribe-Stewed Noodles 资源](https://oss.stewednoodles.com/2025/02/11/StewedNoodles20250211170917.webp)

Of course, that means starting with a test:

当然,这意味着要从测试开始:

func testSplitterExists() {

XCTAssertEqual(app.splitters.count, 1, "There should be 1 split view to manage our input and output.")

}

This now checks for the existence of a splitter, so we can adjust our app code a little to match:

现在会检查是否存在分割器,因此我们可以稍稍调整应用程序代码以匹配:

HSplitView {

TextEditor(text: $input)

SimpleWebView(content: input)

}

Now that test passes, so we’re done with UI testing.

现在测试通过了,用户界面测试也就完成了。

![图片[7]-LiveScribe-Stewed Noodles 资源](https://oss.stewednoodles.com/2025/02/11/StewedNoodles20250211171850.webp)

Over to unit tests 转到单元测试

At this point we’ve written four tests, all of which verify that our user interface matches what it should be. That’s nice, but the real meat of this app lies in its logic – it’s supposed to convert Markdown into HTML, rather than just copy text from the input box into the output box.

至此,我们已经编写了四个测试,所有测试都验证了我们的用户界面与应有的界面相匹配。这很好,但这个应用程序真正的核心在于它的逻辑–它应该把 Markdown 转换成 HTML,而不仅仅是把文本从输入框复制到输出框。

This is where unit tests come in: unlike UI tests, unit tests have direct access to the internals of our project, so they can run code directly rather than scanning the screen.

这就是单元测试的用武之地:与用户界面测试不同,单元测试可以直接访问项目的内部结构,因此可以直接运行代码,而不是扫描屏幕。

Earlier I said that UI tests are annoying because they need XCTest, they take over your whole screen, and they can also be flaky because of the way they scan the screen. Well, unit tests suffer from none of those problems: they use the newer, smarter Swift Testing framework, they don’t take over the screen while running, and they should never be flaky because they are literally running your code and checking the output directly.

之前我说过,用户界面测试很烦人,因为它们需要 XCTest,会占用整个屏幕,而且由于扫描屏幕的方式,它们还可能会不稳定。而单元测试却没有这些问题:它们使用了更新、更智能的 Swift 测试框架,运行时不会占用屏幕,而且因为它们实际上是在运行你的代码并直接检查输出,所以绝对不会不稳定。

This means unit tests should be your first port of call for your code – you want to have way more unit tests than UI tests. Think multiples of 100 rather than multiples of 2 or 3!

这意味着单元测试应该是代码的第一道关口–单元测试的数量要远远多于用户界面测试。想想 100 的倍数,而不是 2 或 3 的倍数!

Let’s write our first unit test now. This is done in a separate target, so go back to the File menu and choose New > Target. This time select Unit Testing Bundle and give it the name LiveScribeTests. Make sure Swift Testing is chosen for Testing System, then click Finish.

现在让我们编写第一个单元测试。这是在一个单独的目标中完成的,所以回到 “File “菜单,选择 “New > Target”。这次选择单元测试捆绑包,并将其命名为 LiveScribeTests。确保测试系统选择 Swift Testing,然后单击 “完成”。

This will create another group in your project, along with another example test. This time it looks a little different, because we’re using Swift Testing rather than XCTest:

这将在项目中创建另一个组,以及另一个示例测试。这次看起来有点不同,因为我们使用的是 Swift Testing 而不是 XCTest:

- Our

LiveScribeTeststype is a struct rather than a class.

我们的LiveScribeTests类型是一个结构体,而不是一个类。 - The example test method is simply called

example()rather thantestExample().

示例测试方法简单地称为example()而不是testExample()。 - It uses the

@Testmacro, which is what makes it discoverable by Swift Testing.

它使用@Test宏,因此可以被 Swift Testing 发现。

There’s a good chance you won’t see one of those diamond buttons next to testExample() – there’s a longstanding Xcode bug where it won’t realize tests are there until you close and re-open the project, or sometimes until you run the test for the first time.

您很有可能看不到testExample()旁边的菱形按钮–Xcode 存在一个长期存在的 bug,即在您关闭并重新打开项目之前,或者有时在您第一次运行测试之前,它都不会意识到测试的存在。

Once you can see the diamond button for example(), please click it and the test ought to run and pass. You might notice two things:

一旦您看到 example() 的钻石按钮,请点击它,测试应该会运行并通过。您可能会注意到两件事:

- It happens very quickly. 它发生得非常快。

- It doesn’t take over your screen.

它不会占据你的屏幕。

Both of those happen for the same reason: unit tests don’t use the macOS accessibility system to do their work, and can instead create instance of types directly from your project. This makes them thousands of times faster than UI tests, which is important – you should be able to run 1000 or so unit tests a second, which means you can effectively write as many tests as you want and use them often as you work.

这两种情况发生的原因是一样的:单元测试不使用 macOS 辅助系统来完成工作,而是直接从你的项目中创建类型实例。这使得单元测试的速度比 UI 测试快数千倍,这一点非常重要–你应该能在一秒钟内运行 1000 个左右的单元测试,这意味着你可以随心所欲地编写测试,并 在工作中经常使用它们。

So, from here on we’re not going to use the diamond buttons any more to run individual tests. Instead, I want you to press Cmd+U, which tells Xcode to run all your tests.

因此,从现在开始,我们将不再使用菱形按钮来运行单个测试。相反,我希望您按下 Cmd+U 即可让 Xcode 运行所有测试。

Of course, “all your tests” include the UI tests we wrote earlier, so this means testing is back to being annoying – it’s not a great place to be.

当然,”你的所有测试 “包括我们之前写的用户界面测试,所以这意味着测试又回到了恼人的状态–这可不是一个好地方。

So, we’re going to disable our UI tests for the time being. To do that, go to the Product menu, hold down Option, then click “Test…” to bring up the test configuration options for our project. You should see “LiveScribe (Autocreated)” under Test Plans, along with a tiny arrow next to it – click that arrow now, which will let us edit our test plan.

因此,我们要暂时禁用 UI 测试。为此,请进入 “Product “菜单,按住 “Option “键,然后单击 “Test…”,调出项目的测试配置选项。你应该会在测试计划下看到 “LiveScribe(Autocreated)”,旁边还有一个小箭头–点击该箭头,我们就可以编辑测试计划了。

As soon as you do that, Xcode will tell you the test plan is in-memory only and not saved, which is the case because it’s autogenerated rather than something we configured. To make changes here we need to actually save a modified test plan somewhere, so please click the Save button and save the resulting file somewhere in your project.

一旦你这样做了,Xcode 就会告诉你测试计划只在内存中,并没有保存,这是因为它是自动生成的,而不是我们配置的。要在这里进行修改,我们需要将修改后的测试计划保存在某个地方,因此请单击 “Save “按钮,并将生成的文件保存在项目中的某个地方。

Now that’s done, you’ll see we can adjust which tests get run. By default it’s all the tests, but I want you uncheck the checkbox next to LiveScribeUITests, because we don’t want them to run for the remainder of this project – you’ll want to re-enable that in your own tests, of course.

完成后,你会看到我们可以调整运行哪些测试。默认情况下是所有测试,但我希望你取消选中 LiveScribeUITests 旁边的复选框,因为我们不希望它们在本项目的剩余时间内运行,当然,你需要在自己的测试中重新启用该选项。

Now that’s done, press Cmd+U again and you’ll see it skips past all the UI tests – our one little unit tests runs without taking over the whole screen.

现在,再次按下 Cmd+U 键,你会看到它跳过了所有的用户界面测试–我们的一个小单元测试在运行时不会占据整个屏幕。

So now let’s go ahead and write our first actual unit test: is our app able to convert an empty string of Markdown into empty HTML?

现在,让我们开始编写第一个实际的单元测试:我们的应用程序能否将 Markdown 的空字符串转换为空 HTML?

Now, we’re in unit test territory, so we want to stay clear of SwiftUI as much as possible. For Markdown parsing, that means having a specialized type do all the parsing for us rather than cram things into views, so let’s start with this test:

现在,我们进入了单元测试领域,所以我们要尽可能远离 SwiftUI。对于 Markdown 解析来说,这意味着我们需要一个专门的类型来完成所有解析工作,而不是把所有东西都塞进视图中,所以让我们从这个测试开始:

@Test func empty() {

let markdown = MarkdownParser(markdown: "")

#expect(markdown.text == "")

}

expect 预期

That test isn’t just going to fail – it’s not even going to build! You see, we haven’t made a MarkdownParser type just yet, nor given it an initializer or a text property.

这个测试不仅会失败,甚至连构建都做不到!要知道,我们还没有创建MarkdownParser类型,也没有给它初始化器或text

As usual, we need to write just enough code to make that test pass. So, create a new Swift file in your main app target called MarkdownParser.swift, then give it this code:

像往常一样,我们需要编写足够多的代码来使测试通过。因此,在您的主应用程序目标中新建一个 Swift 文件,名为 MarkdownParser.swift,然后为其添加以下代码:

struct MarkdownParser {

var text = ""

init(markdown: String) {

}

}

You might think that would be enough for your test to pass, but again it still won’t even build – your test still won’t recognize the MarkdownParser exists.

您可能会认为这足以让您的测试通过,但同样的,它仍然无法构建–您的测试仍然无法识别MarkdownParser的存在。

To fix this, we need to add another import line to the file, to bring in all the code from the main project:

要解决这个问题,我们需要在文件中添加另一行导入,以引入主项目中的所有代码:

@testable import LiveScribe

That not only brings in all the code from the main app target, but the @testable attribute exposes its internals for us to poke around. In this case, it means we get access to the MarkdownParser struct, so our test code now builds and passes correctly.

这不仅引入了主应用程序目标中的所有代码,而且@testable属性还暴露了其内部结构,供我们探查。在本例中,这意味着我们可以访问MarkdownParser结构,因此我们的测试代码现在可以正确构建并通过。

Next, let’s write a test for a simple piece of text, which should be converted into a paragraph of HTML:

接下来,让我们为一段简单的文本编写一个测试,将其转换成一段 HTML:

@Test func singleParagraph() {

let uuid = UUID().uuidString

let markdown = MarkdownParser(markdown: uuid)

let output = "<p>\(uuid)</p>"

#expect(markdown.text == output)

}

Note: Your test file probably won’t include a Foundation import, so please add one in order to gain access to UUID.

注意:您的测试文件可能不包括 Foundation 导入,因此请添加一个,以便访问UUID。

Again, that generates a random string rather than forcing something hard-coded, and it will fail because our parser doesn’t know what to do with the text.

同样,这会生成一个随机字符串,而不是硬编码,而且会失败,因为我们的解析器不知道如何处理文本。

We need to write just enough code in MarkdownParser to make this test pass. We could try and use this:

我们只需在MarkdownParser中编写足够的代码,就能使测试通过。我们可以尝试使用

init(markdown: String) {

text = "<p>\(markdown)</p>"

}

And while that will definitely make our new test pass, it will make our old test fail – empty Markdown should produce empty HTML.

虽然这肯定会让我们的新测试通过,但也会让我们的旧测试 失败 –空的 Markdown 应该产生空的 HTML。

So, let’s use a slightly more inventive cheat that makes both tests pass:

因此,让我们使用一种稍有创意的作弊方法,使这两项测试都能通过:

init(markdown: String) {

if markdown.isEmpty == false {

text = "<p>\(markdown)</p>"

}

}

Great! And that’s not being silly – this really is just enough code for the test to pass, which is our job.

好极了!这并不是傻话–我们的工作就是编写足够的代码,让测试通过。

But that little cheat won’t last long, because our next test will be to ensure we handle multiple paragraphs correctly:

不过,这个小把戏不会持续太久,因为我们的下一个测试将是确保正确处理多个段落:

@Test func multipleParagraphs() {

let uuid = UUID().uuidString

let input = Array(repeating: uuid, count: 3).joined(separator: "\n\n")

let output = Array(repeating: "<p>\(uuid)</p>", count: 3).joined()

let markdown = MarkdownParser(markdown: input)

#expect(markdown.text == output)

}

Now, obviously we could carry on extending our cheat further and further, but we’re back to the arms race problem – we aren’t here to write junk code just to get little green checkmarks in Xcode!

现在,我们显然可以继续进一步扩展我们的作弊器,但我们又回到了军备竞赛的问题上–我们不是为了在 Xcode 中获得绿色小复选标记而编写垃圾代码!

Instead, let’s upgrade our Markdown parser so it actually handles Markdown parsing the way it’s supposed to. Markdown itself is a huge specification with a whole bunch of corner cases, but helpfully we don’t need to care too much – Apple has written a really excellent Markdown parser for us that cleanly wraps a standard Markdown implementation created and maintained by GitHub.

相反,让我们升级 Markdown 解析器,这样它就能真正按照应有的方式处理 Markdown 解析。Markdown 本身就是一个庞大的规范,其中有一大堆的死角,但好在我们不需要太在意–Apple 已经为我们编写了一个非常出色的 Markdown 解析器,它干净利落地封装了由 GitHub 创建和维护的标准 Markdown 实现。

Converting Markdown to HTML 将 Markdown 转换为 HTML

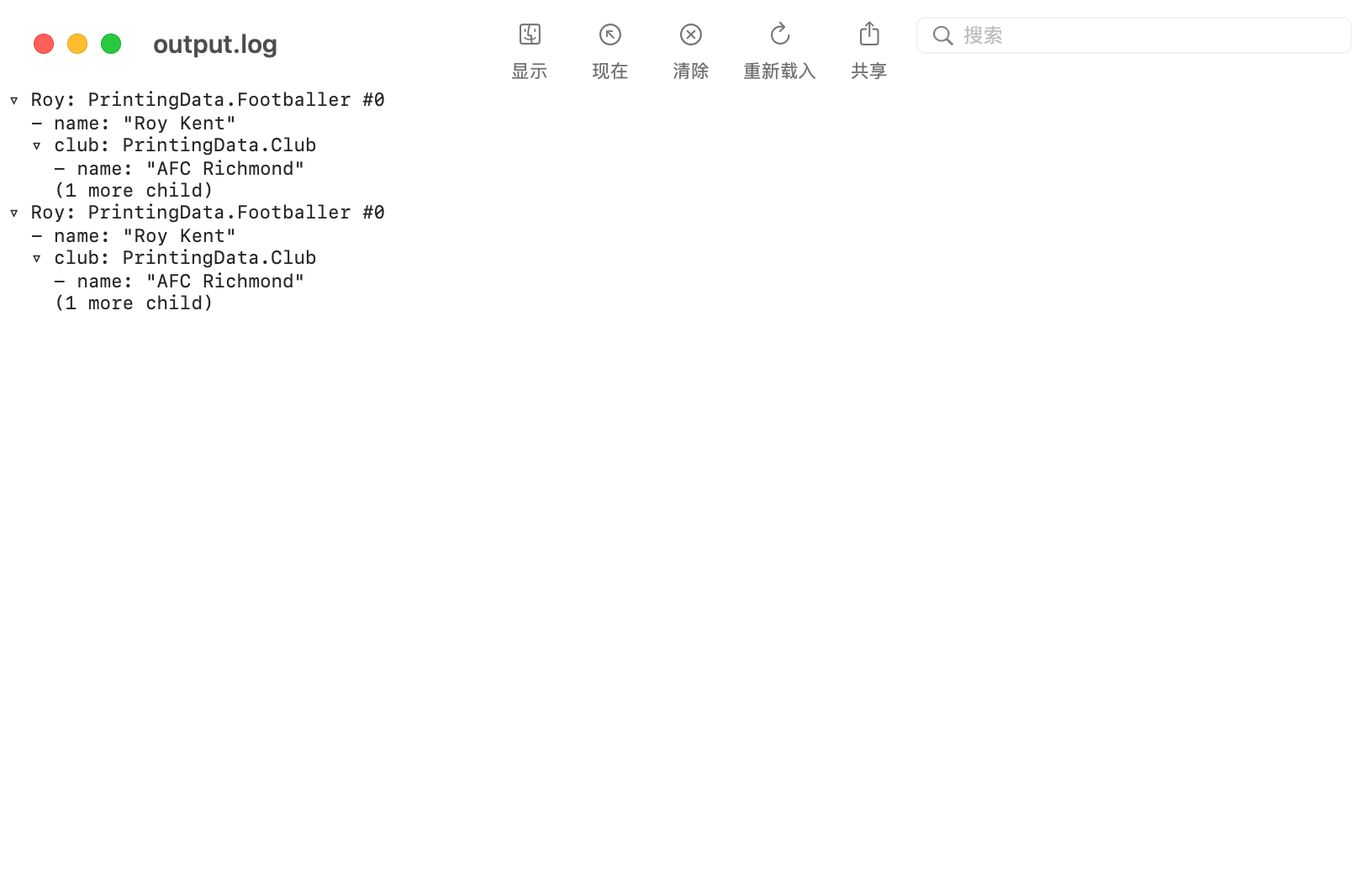

So, our first step here is to bring in Apple’s Swift Markdown framework, which can be done through Swift Package Manager. Go the File menu and choose “Add Package Dependencies…”.

因此,我们的第一步是引入苹果的 Swift Markdown 框架,这可以通过 Swift 软件包管理器完成。进入 “File “菜单,选择 “Add Package Dependencies…”。

Despite being an official Swift package from Apple, Swift Markdown doesn’t (currently) appear in the Apple Swift Packages collection. You need to type its URL into the “Search or enter package URL” box instead: https://github.com/swiftlang/swift-markdown.

尽管 Swift Markdown 是 Apple 的官方 Swift 软件包,但它目前并未出现在 Apple Swift 软件包集合中。您需要在 “搜索或输入软件包 URL “框中键入其 URL:https://github.com/swiftlang/swift-markdown。

Enter that, click Add Package, then select “LiveScribe” under the Add To Target column, so it’s ready for us to use in our main app. And now we need to write just enough code in the MarkdownParser struct to make it handle paragraphs of text.

输入后,点击 ” Add Package”,然后在 “Add To Target “一栏中选择 “LiveScribe”,这样我们就可以在主应用程序中使用它了。现在,我们只需在MarkdownParser结构中编写足够的代码,使其能够处理文本段落。

![图片[8]-LiveScribe-Stewed Noodles 资源](https://oss.stewednoodles.com/2025/02/11/StewedNoodles20250211174721.webp)

The Swift Markdown framework uses a common design pattern called the visitor pattern, which is where it works its way through the input text, making callbacks to us whenever it finds something interesting. We can then go ahead and process its findings as they stream in, building up our output HTML.

Swift Markdown 框架使用一种名为 “访问者模式” 的常见设计模式,即在输入文本的过程中,每当发现有趣的内容时,就会回调给我们。然后,我们就可以继续处理输入的结果,创建输出 HTML。

In order for Swift Markdown to be able to send data our way, we need to add import Markdown to the top of MarkdownParser.swift, then make our MarkdownParser struct to conform to the main protocol from Swift Markdown:

为了让 Swift Markdown 能够以我们的方式发送数据,我们需要在 MarkdownParser.swift 的顶部添加import Markdown,然后让我们的MarkdownParser结构符合 Swift Markdown 的主要协议:

struct MarkdownParser: MarkupVisitor {

Now that’s done, we can set our text property to be the result of visiting all the different element types inside our Markdown document. This is done by creating a document, then visiting it – that will kick off a whole chain of events as the parser finds different kinds of things inside the Markdown we provide.

现在,我们可以将text

So, change your MarkdownParser initializer to this:

因此,请将MarkdownParser初始化器改成这样:

init(markdown: String) {

let document = Document(parsing: markdown)

text = visit(document)

}

And now it’s mostly our job to handle as many Markdown element types as we want. I say “mostly” because one is required: defaultVisit(), which determines what to do when the parser finds an element that we haven’t specifically handled. Right now we haven’t specifically handled any element type, so this will be called for everything.

现在,我们的工作主要是处理尽可能多的 Markdown 元素类型。我说 “主要 “是因为有一项是必需的:defaultVisit(),它决定了当解析器发现我们没有特别处理的元素时该怎么做。现在,我们还没有特别处理过任何元素类型,所以所有元素都会调用 defaultVisit()。

We’re going to implement a very simple version here, and it will form the foundation of the way we parse lots of other sorts of Markdown. You see, Markdown is a structured form of text where things naturally make a tree – a document might have many paragraphs, one paragraph might have some text that’s in bold, part of the bold text might be in italic, and part of the bold italic text might be a link to a website.

我们将在这里实现一个非常简单的版本,它将成为我们解析大量其他类型 Markdown 的基础。你看,Markdown 是一种结构化的文本形式,其中的内容自然而然地构成了一棵树–一个文档可能有很多段落,其中一段可能有一些粗体文字,部分粗体文字可能是斜体,部分斜体粗体文字可能是一个网站链接。

From an abstract perspective, we can say the document is the parent of the paragraphs, the paragraphs are the parent of the bold text, the bold text is the parent of the italic text, and the italic text is the parent of the link.

从抽象的角度看,我们可以说文档是段落的父级,段落是粗体文本的父级,粗体文本是斜体文本的父级,斜体文本是链接的父级。

All this matters because when we visit a given node in Markdown, we also want to visit its children. So, for our defaultVisit() method will make an empty string, then loop over every child of this element and the result of visiting it to our string, then send back the final result.

所有这些都很重要,因为当我们访问 Markdown 中的一个给定节点时,我们也想访问它的子节点。因此,我们的defaultVisit()方法将生成一个空字符串,然后循环遍历该元素的每个子元素,并将访问结果转换为我们的字符串,然后发送回最终结果。

Add this to MarkdownParser now:

立即将此添加到MarkdownParser:

mutating public func defaultVisit(_ markup: any Markup) -> String {

var result = ""

for child in markup.children {

result += visit(child)

}

return result

}

Go ahead and run the test now. It won’t pass, but I do at least want you to see the result – it should say that the output for our parser was an empty string, which obviously fails the test of finding multiple paragraphs of a UUID.

现在继续运行测试。它不会通过,但我至少想让你看看结果–它应该会说,我们的解析器的输出是一个空字符串,这显然没有通过查找 UUID 多个段落的测试。

The reason it’s an empty string is important. Our code starts by visiting a paragraph of text, which is unhandled right now so defaultVisit() gets called. That creates an empty string, and goes on to visit all the children of the paragraph, which is the UUID text inside it.

之所以是空字符串,原因很重要。我们的代码从访问一段文本开始,这段文本现在还未处理,所以defaultVisit()会被调用。这会创建一个空字符串,然后继续访问该段的所有子代,也就是其中的 UUID 文本。

Again, our parser doesn’t know how to handle text, so it calls defaultVisit(), which makes an empty string, visits all the children inside the text, then sends back the result. There aren’t any children inside the text – there’s no bold or italic, for example – so each piece of text sends back an empty string to the paragraph parser, which adds that to its existing empty string, so it’s no surprise the overall result is simply an empty string.

同样,我们的解析器不知道如何处理文本,所以它调用defaultVisit(),它生成一个空字符串,访问文本中的所有子代,然后将结果发回。文本中没有任何子文本,例如没有粗体或斜体,因此每段文本都会向段落分析器发回一个空字符串,段落分析器会将其添加到现有的空字符串中,因此整个结果是一个空字符串也就不足为奇了。

To begin to make our test pass, we need to add two new methods to our MarkdownParser struct. First, we need to teach it what to do when it visits some text, which is the UUID string from our test.

为了使测试通过,我们需要在MarkdownParser结构中添加两个新方法。首先,我们需要教它在访问一些文本(即我们测试中的 UUID 字符串)时该怎么做。

After the defaultVisit() method, type “text”, and Xcode’s autocomplete should prompt to complete the visitText() method. This is the one Swift Markdown will call when it finds some text it wants us to handle.

在defaultVisit()方法之后,输入 “text”,Xcode 的自动完成功能会提示完成visitText()方法。当 Swift Markdown 发现需要我们处理的文本时,就会调用该方法。

What should we do when we find some text? Well, use it! We already have a string, so we can ask Swift Markdown to send back the text itself like this:

当我们找到一些文字时该怎么办?那就使用它!我们已经有了一个字符串,所以我们可以像这样要求 Swift Markdown 返回文本本身:

func visitText(_ text: Text) -> String {

text.plainText

}

Note: This method doesn’t need to be marked mutating because it doesn’t call visit() on its children.

注意:此方法不需要标记为mutating,因为它不会对其子方法调用visit()。

Go ahead and try the test again, and you’ll see it’s still failing. It is better, though, because now you’ll see the UUID repeated three times in our output.

再试一次,你会发现测试仍然失败。不过现在好多了,因为你会看到 UUID 在输出中重复了三次。

Actually making the test pass means adding another visit method to our parser: visitParagraph(). This is almost the same as the defaultVisit() method, except this time we need to start with <p> before parsing its children, and add </p> after parsing its children.

实际上,要使测试通过,我们需要在解析器中添加另一个访问方法:visitParagraph()。这与defaultVisit()方法几乎相同,只是这次我们需要在解析其子段之前以<p>开始,并在解析其子段 之后 添加</p>。

Add this to MarkdownParser now:

立即将此添加到MarkdownParser:

mutating func visitParagraph(_ paragraph: Paragraph) -> String {

var result = "<p>"

for child in paragraph.children {

result += visit(child)

}

result += "</p>"

return result

}

Going back to the tree perspective, this new method will be called first, then it will go on to visit the children, which makes visitText() get called.

回到树的视角,这个新方法将首先被调用,然后它将继续访问子代,这使得visitText()被调用。

And now the test should run and pass successfully – we are now generating actual HTML from Markdown!

现在,测试应能成功运行并通过–我们现在正从 Markdown 生成实际的 HTML!

Before you run the app, I want to add two more visit methods that show you how useful the app is: one for bold, and one for italics. In Markdown terms this is strong and emphasis, but both of these are almost exactly the same as our existing paragraph-visiting code – all you need to do is change the <p> tag to either <strong> or <em> as appropriate.

在运行该程序之前,我想再添加两个访问方法,向您展示该程序的实用性:一个用于粗体,一个用于斜体。在 Markdown 术语中,这两种方法分别是strong和emphasis,但这两种方法与我们现有的段落访问代码几乎完全相同,您只需根据情况将<p>标记更改为<strong>或<em>即可。

Again, let’s start by writing tests:

还是让我们从编写测试开始吧:

@Test func strong() {

let uuid = UUID().uuidString

let input = "**\(uuid)**"

let output = "<p><strong>\(uuid)</strong></p>"

let markdown = MarkdownParser(markdown: input)

#expect(markdown.text == output)

}

@Test func emphasis() {

let uuid = UUID().uuidString

let input = "*\(uuid)*"

let output = "<p><em>\(uuid)</em></p>"

let markdown = MarkdownParser(markdown: input)

#expect(markdown.text == output)

}

Those two are good, but while we’re here we might as well test them both together:

这两个都不错,但既然来了,我们不妨把它们一起测试一下:

@Test func strongEmphasis() {

let uuid = UUID().uuidString

let input = "***\(uuid)***"

let output = "<p><em><strong>\(uuid)</strong></em></p>"

let markdown = MarkdownParser(markdown: input)

#expect(markdown.text == output)

}

And to make those pass, we need to add two new visit methods to our parser. You can copy these from visitParagraph() if you want – just make sure you change the opening and closing HTML tags!

为了使这些方法通过,我们需要在解析器中添加两个新的访问方法。您可以从visitParagraph() 中复制这些方法,只需确保更改开头和结尾的 HTML 标记!

mutating public func visitStrong(_ strong: Strong) -> String {

var result = "<strong>"

for child in strong.children {

result += visit(child)

}

result += "</strong>"

return result

}

mutating public func visitEmphasis(_ emphasis: Emphasis) -> String {

var result = "<em>"

for child in emphasis.children {

result += visit(child)

}

result += "</em>"

return result

}

Our tests should now all pass, which is great!

我们的测试现在应该全部通过了,这真是太好了!

Now go ahead and run the app. You might notice that Markdown parsing never happens, which shows a rather significant shortcoming in our app!

现在继续运行应用程序。你可能会发现 Markdown 解析从未发生过,这说明我们的应用程序存在一个相当大的缺陷!

This happens because we haven’t actually connected the Markdown parser to our text editor – we’re just copying the text from input to output. This means all our tests are correct, but still not good enough to test what we actually care about.

出现这种情况是因为我们没有将 Markdown 解析器与文本编辑器连接起来–我们只是将文本从输入复制到输出。这意味着我们的所有测试都是正确的,但仍然不足以测试我们真正关心的内容。

The fix here is simple, but remember: we can’t write production code unless we’re doing it to make a test pass. So, we need to write a test with some Markdown that doesn’t have a simple 1-to-1 mapping with its input text. Bold and italic both don’t, but they are hard to test, so instead let’s write a test for links – Markdown links have a specific format, but end up appearing as clickable hyperlinks in HTML.

解决方法很简单,但请记住:除非是为了让测试通过,否则我们不能编写生产代码。因此,我们需要用一些不能与输入文本进行简单 1 对 1 映射的 Markdown 来编写测试。粗体和斜体都不是,但它们很难测试,所以我们来写一个链接测试–Markdown 链接有特定的格式,但最终会在 HTML 中显示为可点击的超链接。

Start by adding this test alongside the others:

首先,将该测试与其他测试一起添加:

@Test func link() {

let uuid = UUID().uuidString

let input = "[\(uuid)](https://hackingwithswift.com/\(uuid))"

let output = "<p><a href=\"https://hackingwithswift.com/\(uuid)\">\(uuid)</a></p>"

let markdown = MarkdownParser(markdown: input)

#expect(markdown.text == output)

}

That creates a Markdown link, and checks that it comes back as a HTML link. It will fail, so let’s go ahead and write the correct visit method in MarkdownParser.

这将创建一个 Markdown 链接,并检查它是否以 HTML 链接的形式返回。这会失败,所以让我们继续在MarkdownParser 中编写正确的访问方法。

This time we’ll be handed a Link object, which will tell us the destination URL. We can then visit its children, which include the text inside the link. Add this to MarkdownParser to handle it all:

这次我们将得到一个Link对象,它将告诉我们目标 URL。然后我们可以访问它的子对象,其中包括链接内的文本。将此添加到MarkdownParser中,以处理这一切:

mutating public func visitLink(_ link: Link) -> String {

var result = #"<a href="\#(link.destination ?? "#")">"#

for child in link.children {

result += visit(child)

}

result += "</a>"

return result

}

That’s enough to make our test pass, but it still doesn’t solve our problem – our actual app code doesn’t parse the Markdown it’s given.

这足以让我们的测试通过,但仍然不能解决我们的问题–我们的实际应用代码无法解析它所给出的 Markdown。

For that to happen we need a failing UI test with links: we need to type a link into our input text editor, and check that afterwards we have a tappable link to work with.

为此,我们需要对链接进行一个失败的用户界面测试:我们需要在输入文本编辑器中输入一个链接,然后检查是否有一个可点击的链接可供使用。

This is similar to the other UI tests we’ve written: wait for the web view to exist, tap the text editor, use typeText(), etc. Except this time the assertion we’re making is on app.links.count – literally how many tappable links exist in our UI, whether in the web view or elsewhere.

这与我们编写的其他 UI 测试类似:等待网页视图存在、点击文本编辑器、使用typeText() 等。只不过这次我们的断言是关于app.links.count的,也就是用户界面中存在多少个可点击的链接,无论是在网页视图中还是其他地方。

Add this new method to LiveScribeUITests.swift file:

将这一新方法添加到LiveScribeUITests.swift文件中:

func testLinksWork() {

_ = app.webViews.firstMatch.waitForExistence(timeout: 1)

app.textViews.firstMatch.tap()

app.typeText("[Learn Swift](https://www.hackingwithswift.com)")

XCTAssertEqual(app.links.count, 1, "Creating a link should make it tappable.")

}

I know we disabled the UI tests earlier, but that only disables it for the default Test command that’s run through Cmd+U – we can still save this file then click the diamond button next to the test to run it manually.

我知道我们之前禁用了用户界面测试,但这只是禁用了通过 Cmd+U 运行的默认测试命令,我们仍然可以保存此文件,然后单击测试旁边的钻石按钮手动运行。

Yes, we’re temporary back to having tests take over your computer, but now the test will fail – and more importantly the only way to make it pass is to connect the text editor’s text to our Markdown parser, rather than handing it straight to the web view.

是的,我们暂时又回到了让测试接管你的电脑的状态,但现在测试会失败–更重要的是,让测试通过的唯一方法是将文本编辑器的文本连接到我们的 Markdown 分析器,而不是直接交给网络视图。

So, open ContentView and change the SimpleWebView code to this:

因此,打开ContentView并将SimpleWebView的代码更改为这样:

SimpleWebView(content: MarkdownParser(markdown: input).text)

And now not only will all our tests pass, but the app is actually useful! Go ahead and run it – you’ll find you can use bold, italic, and links to have them all appear nicely formatted as you type.

现在,我们不仅通过了所有测试,而且这个应用程序还真的很有用!继续运行它吧–你会发现你可以使用粗体、斜体和链接,让它们在你输入时都显示出很好的格式。

Drawing the rest of the owl 绘制猫头鹰的其余部分

At this point, all that remains for the app is to add in as many of the other Markdown visitor methods as you want – after writing tests for them, of course.

至此,应用程序只需根据自己的需要添加其他 Markdown 访问方法,当然是在为它们编写测试之后。

Before we’re done, though, I want to show one more important thing. For example, let’s say we want to write tests for headings: HTML has several of them, with <h1> being the biggest, and <h6> being the smallest.

不过,在结束之前,我还想说明一件重要的事情。例如,假设我们要编写标题测试:HTML 有几个标题,其中<h1>最大,而<h6>最小。

It would be cumbersome to write individual tests for each heading level, but helpfully Swift Testing provides an option called parameterized tests – we can make our test method accept a parameter, and use the @Test macro to pass in a range of values as individual tests.

为每个标题级别编写单独的测试会很麻烦,但 Swift 测试提供了一个叫做 参数化测试的 选项,这很有帮助–我们可以让测试方法接受一个参数,然后使用@Test宏将一系列值作为单独的测试传入。

Add this to the LiveScribeTests struct now:

现在就将其添加到LiveScribeTests结构中:

@Test(arguments: 1...6)

func heading(number: Int) {

// more code to come

}

As you can see, that tells the method it should expect an integer to be passed in. That integer comes from the @Test macro – you can see I’ve given it the range 1 through 6, which means it will call heading(number: 1), heading(number: 2), etc, until it has finished going through the entire range.

正如你所看到的,这告诉该方法它应该期望传递一个整数。这个整数来自@Test宏,你可以看到我给了它 1 到 6 的范围,这意味着它会调用heading(number:1)、heading(number:2 ) 等,直到完成整个范围的遍历。

In Markdown headings are written using one or more # symbols, so we can generate the correct Markdown for a heading with random contents like this:

在 Markdown 中,标题使用一个或多个#符号来书写,因此我们可以为这样一个内容随机的标题生成正确的 Markdown:

let uuid = UUID().uuidString

let headingString = String(repeating: "#", count: number)

let input = "\(headingString) \(uuid)"

Each heading level will then match <h1> and similar in HTML, so our output is this:

然后,每个标题级别都将匹配 HTML 中的<h1>和类似内容,因此我们的输出结果是这样的:

let output = "<h\(number)>\(uuid)</h\(number)>"

And then we can repeat our usual work of parsing the Markdown and asserting that we got the correct HTML back:

然后,我们就可以重复我们通常的工作,即解析 Markdown 并断言我们得到了正确的 HTML 返回:

let markdown = MarkdownParser(markdown: input)

#expect(markdown.text == output)

That’s going to fail as usual, but the fix is almost the same thing we’ve done several times already – the only change this time is that the element type we’re visiting is Heading, which has a level property that tells us whether it’s a level 1 heading, a level 2 heading, etc.

这将像往常一样失败,但修复方法几乎与我们已经做过多次的相同–这次唯一的变化是我们访问的元素类型是Heading,它有一个level属性,可以告诉我们它是一级标题还是二级标题,等等。

So, add this to MarkdownParser:

因此,将此添加到MarkdownParser 中:

mutating public func visitHeading(_ heading: Heading) -> String {

var result = "<h\(heading.level)>"

for child in heading.children {

result += visit(child)

}

result += "</h\(heading.level)>"

return result

}

And now our test will pass. Notice how the Test navigator shows each heading level as individual tests, neatly organized under the heading(number:) method – it’s really nice!

现在我们的测试通过了。注意 “Test navigator “是如何将每个标题级别显示为单独的测试,并在heading(number:)方法下整齐地组织起来的–这真的很棒!

That’s it for this project. Yes, there’s a whole bunch more types of Markdown to parse, but I’ll leave that to you – just make sure you start by writing tests first!

本项目到此为止。是的,还有更多类型的 Markdown 需要解析,但我会把这个留给你,只要确保你先从编写测试开始就可以了!

暂无评论内容